Dialoguing the historical importance of the industry, and the cultural significance of the historic Riverside House site, through undertaking the sympathetic restoration and imaginative repurposing of the grade II listed site for the benefit of the wider community and articulating this in a creative and imaginative way.

Heritage

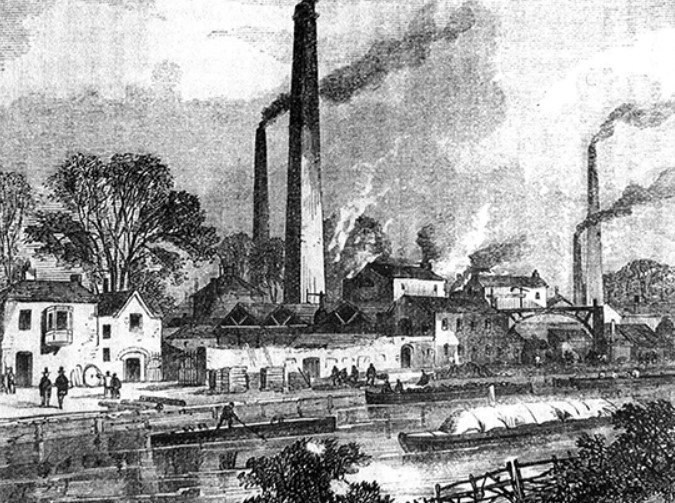

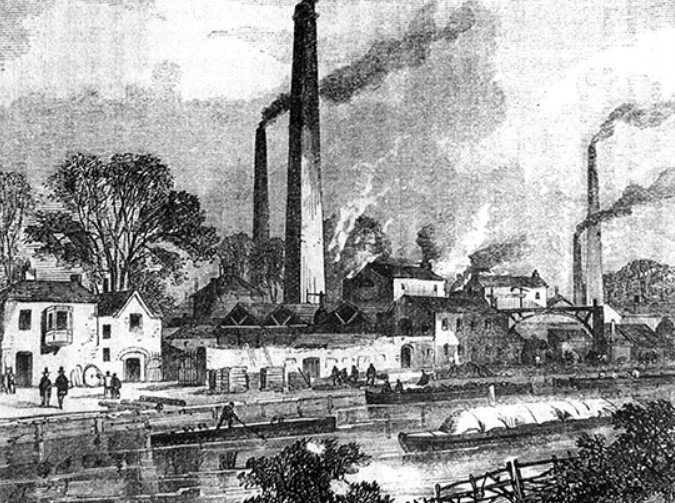

The ironworks at Riverside House consisted of forges, fineries, rolling-mills and foundries which transformed pig iron into casted and wrought iron products. Wrought iron being, at that time, the most widely used form of iron product. In its heyday, the forge and ironworks conglomerate employed 600 people. Historically, the ironworks on the site, and the later partnership of The Foster and Rastrick foundry, are of great importance, both nationally and internationally.

Riverside House itself was the Iron Masters house. The Ironmaster was the manager of a conglomerate that included a foundry and wrought iron puddling works. The house had cast lintels and a staircase that were almost certainly made in the foundry. One window is painted, considered to be because of the window tax. In front of the house is a walled kitchen garden opening onto the canal. The managers house was part of an estate that included orchards, a market garden, piggeries and osier beds. Some of the fruit trees, including pear, damson and apple, remain and hops have been discovered.

Surrounded by tall walls to the north of the site, a dry dock is clearly visible. There would have been enough room to build or repair two boats. The dry dock would have filled and emptied by means of sluice gates in much the same way as a lock. The exit for the water can be found alongside the canal overflow weir, which drains into the River Stour. The entrance to the dry dock is visible alongside the canal and it goes under a humped bridge on the towpath. Next to the dry dock is a courtyard that would have included ancillary workshops and stables.

The base of a canal side crane can be found along the towpath. This loaded the cast iron products, including the Stourbridge Lion, onto narrowboats. The goods were transported to the crane along a narrow-gauge railway track from the foundry which went across the cast bridge that spans the River Stour. The towpath spans two bridges that were entrances to narrow boat basins that went into the heart of the iron works. It was here that pig iron, limestone and coal were delivered, and the manufactured wrought iron rods and bars, made in the iron works, were shipped back out to worldwide markets.

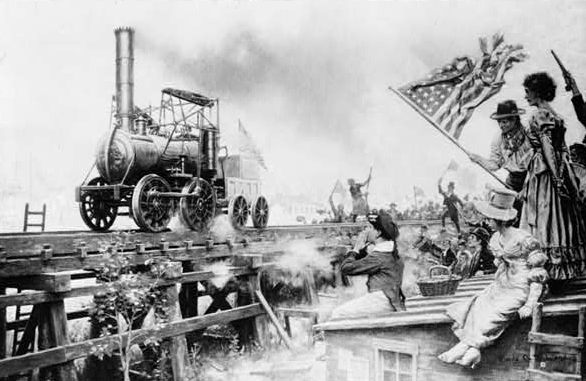

Across the River Stour is the ‘New Foundry’, now the Lion Health Medical Centre. The foundry is the longest serving of any in the world and in its time boasted the largest single metal roof span. The Stourbridge Lion, the first locomotive to run on tracks in the USA, was built here, as well as roof spans for the Customs House in London.

Participating in this environment gives one a sense of historical connection. One gets a sense of what has gone before and that we are part of this process. The team are sensitively repurposing the place in a way that is respectful to its past, whilst creating something innovative and relevant for our time. In the next few years we will be building a heritage centre that will explore the sites geological past, its emerging industrial reliance on the adjacent Stourbridge Canal, and the subsequent decline of industry in the late 20th century.

“Too often the efforts of those with mental health and learning needs are dismissed. This project offers a meaningful opportunity to transform this grade II listed heritage site and leave a lasting legacy for all to visit”

Nikki Burrows - Children, Young People and Families Development Officer

Public Art Sculpture

This vocative description by industrialist James Nasmyth from 1830, brings alive the utter dereliction of the historic Black Country. Included in the sculpture is a blacksmith’s hand holding a hammer and, on the reverse, blacksmiths tongs, These images evoke the historic ironworks that occurred in this place. At the top of the artworks are chains in the same graphic style as the locally beloved Black Country Flag.

Hades is the old name for the waters that preceded the Stourbridge Canal and we loved the idea of resurrecting this old name.

Hades, the God of the Underworld can be seen as a symbol and metaphor for the iron ore, coke and lime extracted from under the ground and transformed into steel. The canal would have also delineated where the ‘dark satanic’ industry began. This landscape would have predated that of the industrial revolution, however, the industry would have been prevalent, albeit on a smaller scale.

Previous to the canals, the Black Country was known as the producer of smaller metal worked items such as nails, locks, hinges, in fact anything that could be transported out of the area by horse and cart. The development of the canals, and subsequently the railways, systemically changed the scale of what was possible to be manufactured. New technologies in mining extraction ensured ever increasing supplies of the required iron ore and coal and an eventual market was made ever more accessible for the finished products.

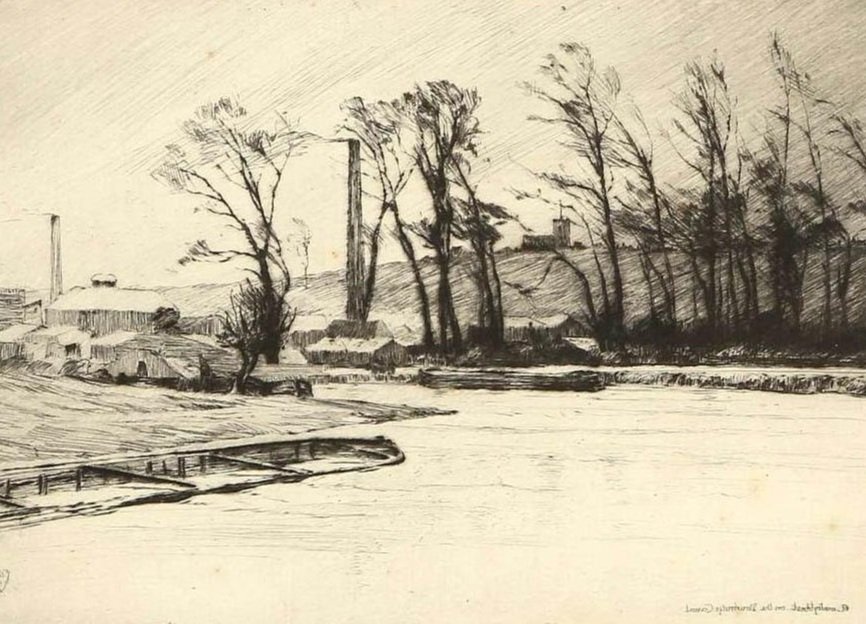

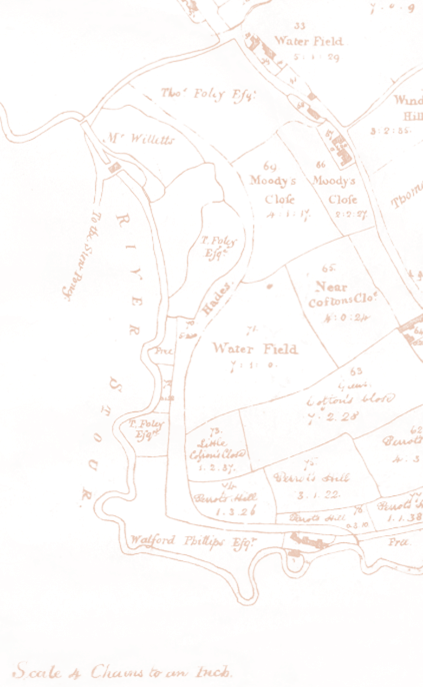

However, the name Hades is perhaps less poetic than the God of the Underworld interpretation. According to local historian Kevin James, the place-names 'Hades' meaning is more prosaic. It comes from the Old English (Anglo-Saxon) word 'hēafod', meaning 'head', which was used for the head-lands at the ends of ploughed furrows. Because of the local topography in this case, the headlands (produced where the plough turned) would have built up roughly parallel to the river (and the ponds of Wollaston Mill), along the line of the later canal. The label 'Hades' is shown on the c. 1760 estate map of Amblecote where part of the canal was subsequently built, The long strip shown on the map seems to have been a century-old remnant of Andrew Yarranton's abortive attempt to make the Stour navigable. His works were destroyed by storms and abandoned after only a few years. The present day width of this particular canal, wider than others, and the abundance of water lilies, may be clues to its previous incarnation.

We hope our interpretation is fitting though, even if it may not be, strictly speaking, accurate in terms of the specific meaning. It resonates well with James Nasmyths text and The God of the Underworld is a perfect imaginative image for the industrialised landscape that was forged from what was mined underfoot.

Artwork designed by Lloyd Stacey and CAD artwork by Claire Price.

![DSC_7478[408002].jpg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/616056bd5e157c2052ceeb18/324bc42b-f389-4981-9c53-c79eb3b7d3e3/DSC_7478%5B408002%5D.jpg)